Keeping an eye on what matters for the economy

Top economists agree that trade and economic growth are inextricably linked. For growth to turn into transformative development, however, more is needed. What’s the importance of international standards in facilitating trade? What is their role in achieving growth in low-income countries? Here’s a glimpse into the worldwide waters of trade.

International trade is the exchange of capital, products and services among two or more countries. It is international because goods cross borders. And it is certainly not new. Trade has existed through history, we can think about the exchange between the Roman Empire and Egypt, or the Silk Road.

However, the international trading system as we know it started to develop after the Second World War when it was used as a tool to promote a lasting peace. For the first time, international rules were put in place. According to Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Krugman, “the postwar trading system grew out of the vision of Cordell Hull, US Secretary of State during Roosevelt’s presidency. He saw commercial links between countries as a way to promote peace. That system, with its multilateral agreements and rules to limit unilateral action, was, from the beginning, a crucial piece of the Pax Americana”.

As a consequence, in 1947 a total of 23 countries adopted the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which later evolved to become the World Trade Organization (WTO). As of today, the WTO counts 164 members with an additional 22 countries that have requested to join.

Global trade growth

Trade has become a major component of GDP for most countries. According to the World Bank, trade represented 24 % of the world’s total GDP in 1962. This number more than doubled, to 57 %, by 2017. For small countries that do not have large internal markets, trade is particularly important, but even for the world’s largest economy, the United States, trade represents 27 % of GDP.

Nevertheless, in recent years the international trading system, as well as globalization more generally, has been increasingly challenged. This is because the undeniable positive effects that trade has on economic growth have not necessarily been accompanied by income redistribution and increased equality in both developed and developing countries. Particularly for developing countries, the increasing participation in international trade, including regional trade, has not clearly translated into transformative development.

For example, in 2018 Vietnam had a record-breaking GDP growth of 7.08 %, yet nine million Vietnamese are still living in extreme poverty, according to a World Bank report. It is important that the integration into global markets be accompanied by comprehensive national policies in areas such as infrastructure, gender equality, support to small and medium-sized enterprises and social programmes such as education and healthcare. Trade cannot solve all the issues alone.

The TBT Agreement

The WTO TBT Agreement establishes rules for the preparation, adoption and application of international standards, technical regulations, national standards and conformity assessment procedures. It aims to ensure that technical regulations, standards and conformity assessment procedures are non-discriminatory and do not create unnecessary obstacles to trade.

Importantly, the Agreement leaves WTO members room to achieve legitimate policy objectives, such as the protection of the environment and consumer safety. However, unnecessary barriers to trade should not be created in the pursuit of such objectives, for example, by overregulating or requiring unnecessary certifications. The Agreement also aims to ease these obstacles to trade by requiring harmonization with international standards and encouraging WTO members to recognize each other’s standards and technical regulations through mutual recognition agreements.

Standards to the rescue

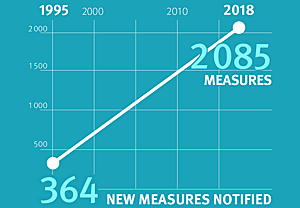

Since the 1970s, technical barriers to trade (TBT), which include technical regulations and standards, have become more prominent. Their effect on global trade patterns is undisputed. The increased reliance on TBT measures becomes clear when one considers the number of notifications of such measures to the WTO.

In 1995, the year the TBT Agreement came into force, 364 new measures were notified. In 2018, the number of new measures soared to 2 085. This enormous rise can be explained by a number of factors: the decrease in the use of tariffs, progressively globalized business structures, the increased participation of emerging markets in global trade regimes, and the growing importance of consumer concerns on issues such as sustainability.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) report, The Unseen Impact of Non-Tariff Measures: Insights from a new database, finds that TBT measures are the most used measures in trade. They are imposed on average on 40 % of product lines, covering approximately 65 % of world imports.

Standards can facilitate trade by reducing transaction costs relating to TBT measures, notably by providing information on product requirements. However, they can also have negative effects on trade when they are carelessly developed or implemented. One way the TBT Agreement aims to diminish these negative effects is through harmonization. The Agreement requires that the technical regulations and standards of WTO members be based on relevant international standards, including those developed by ISO. Moreover, WTO members are required to participate in international standardizing bodies, such as ISO.

As a consequence of the rules of the TBT Agreement, international standards, which are developed as voluntary documents, can effectively become binding rules. International standards can directly impose rules on countries because the TBT Agreement stipulates their use as the basis for development of national regulations and standards. Indirectly, international standards affect trade and markets, as they determine which products can be traded and how, and the variety, quality and safety of products and services.

The verdict of economists

Economists have studied the effects of country-specific and harmonized standards on trade. They found that national standards in the manufacturing sector, even if they are not harmonized with international standards, can promote trade. This is because although they impose adaptation costs on importers, they also provide them with valuable information that, in the absence of a national standard, would be costly and time-consuming to gather [1]. However, the effect is different for primary sectors like agriculture, where adaptation costs exceed the benefits of access to information.

National standards affect developed and developing countries differently. In general, TBT measures are more frequent in products that are typically exported by developing countries such as agricultural produce and textiles. Compliance costs, which are related to technical know-how, infrastructure and even local regulations, are generally more burdensome for developing countries.

Despite this, there is widespread agreement among scholars that having a national standard is better than not having any standard at all. There is also robust evidence that harmonization with international standards promotes international trade flows and that harmonization among developed countries gives developing countries access to more markets.

A study on textile and clothing exports from 47 sub-Saharan countries directed towards the European Union, which back then consisted of 15 members, found that EU standards that are not harmonized with ISO standards reduce African exports, while those that are harmonized have a positive effect on African exports [2]. A similar study from the World Bank, Product Standards, Harmonization and Trade: Evidence from the Extensive Margin, focusing on the textile, clothing and footwear sectors of two hundred countries exporting to the EU, found that a 10 % increase in EU standards harmonized with ISO standards represented an increase of 0.2 % in the variety of imports. This effect is 50 % stronger for low-income countries.

The bottom line

The link between international trade and its integration into global markets, resulting in economic growth, has been clear for a long time. However, trade alone is not enough. As Kofi Annan, former United Nations Secretary-General, once said: “Trade liberalization must be carefully managed as part of comprehensive development strategies that encompass health, education, the empowerment of women, the rule of law and much else besides.”

International standards serve economic growth in two ways. First, they promote trade, specifically exports from developing countries. Therefore, they support economic development. Second, and even more important, they are a tool to achieve sustainable development as they support countries in achieving national policies, such as healthcare, gender equality and the protection of the environment. These national policies are ultimately what transforms economic growth into strong sustainable development – making the 2030 Global Agenda a reality.

- “Information Versus Product Adaptation: The Role of Standards in Trade” by Johannes Moenius (February 2004)

- “Help or Hindrance? The Impact of Harmonised Standards on African Exports” by Witold Czubala, Ben Shepherd and John S. Wilson, Journal of African Economies, Volume 18, Issue 5, November 2009, Pages 711–744 (15 March 2009)

Stats and figures on trade

The international trading system as we know it started to develop after the Second World War when it was used as a tool to promote a lasting peace. Now, trade has become a major component of GDP for most countries.

According to the World Bank, in 2017, trade represented 57 % of the world’s total gross domestic product (GDP).

In 1962, trade represented only 24 % of the world’s total GDP.

History of WTO

23 countries adopted the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in 1947

22 countries have requested to join

Increase in number of measures